Norah Rami (’26), an English and Political Science major, conducted research on censorship under the British Raj with the mentorship of Dr. Caz Batten (Department of English). Her research was supported by the University Scholars program.

The Indian Civil Service was an administration of information; everything was cataloged: native flora, familial customs, and, with the advent of the Indian Census in 1872, the people themselves. Under the Press and Registration of Books Act of 1867 (PRBA), all books and periodicals published in India were registered and cataloged into a standardized database. Between 1868-1905, the British catalogued over 200,000 books, producing over 6 million words of archival text.

These listings were a direct way for the British Imperial government to regulate free speech in colonial India. Catalogues were shared with the Home Department, who used the information to prosecute publishers under Indian Penal Code 124A (IPC). My research asked: What does the usage of the PRBA catalogues in treason trials represent about the relationship between storytelling, interpretation, and power?

With the support of UScholars, I traveled to the British Library to access archival material from the Indian Office Records. I sorted through various cases to understand how the Indian Civil Service identified books for prosecution and learned that the PRBA catalogues were utilized as legal tools to prosecute treasonous texts. Treasonous texts could be prosecuted under 124A IPC, which criminalized writing intended to raise “disaffection” against the British Government. These cases hinged upon a complex negotiation of literary interpretation as publishers and jurists debated the meaning of texts, many of which were poetic or literary in nature.

For example, I found the court records of the prosecution of Nand Gopal, the editor of the Swarajya newspaper in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh. The three articles under prosecution—“Devotion to God,” “The Real Needs of India,” and “The Wave of Nationalism"—concern various critiques of British rule in India, including issues of starvation and poverty. All three texts explicitly disavow rebellion against the British Crown, yet these articles were identified as potentially in violation of Section 124-A. At trial, the judge draws passages from each text and analyzes their potential to raise disaffection against the British. He critiques a metaphor that describes British actions as akin to butchering a cow—which he states will inflame the passions of Hindu Indians. Nand Gopal was sentenced to 10 years as the publisher of this text, which the archive noted was unusually high.

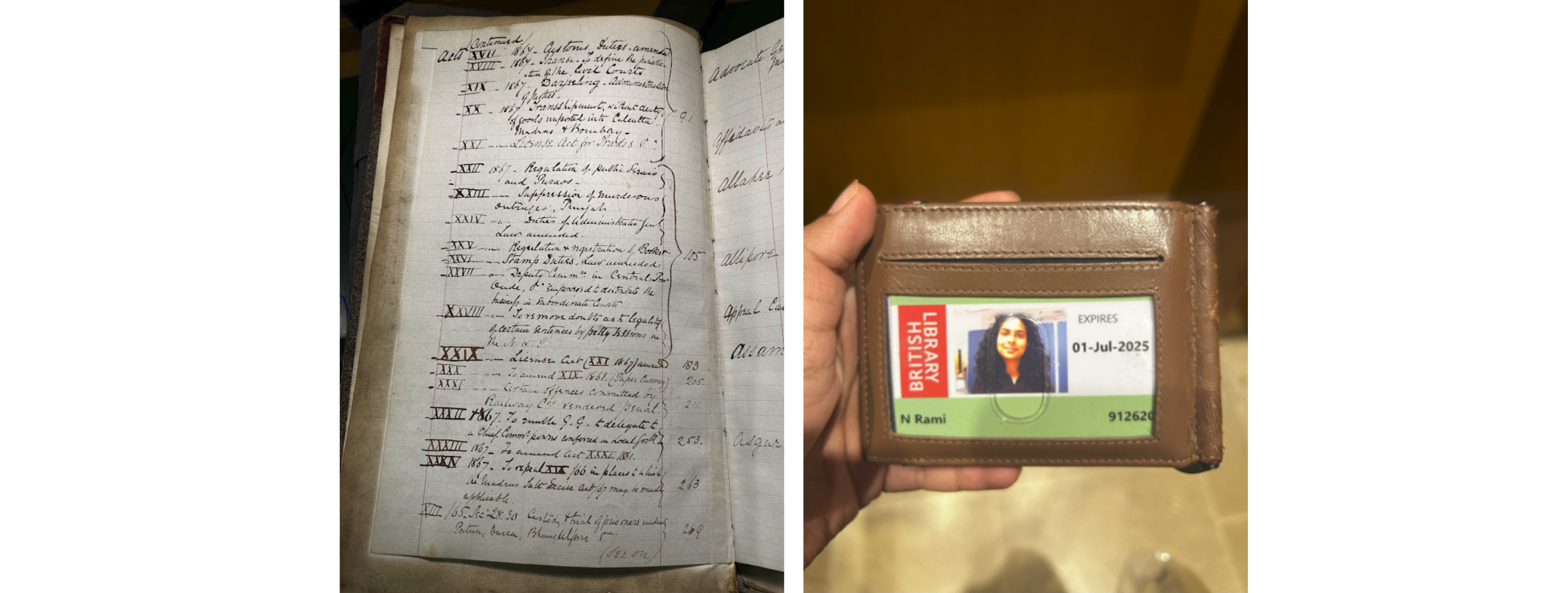

Above left: Norah spent her first day reading through this handwritten catalogue that appeared to be an early precursor to the official ICS catalogues--and was labeled as such in the archives. However, after digging deeper, she found that this catalogue was kept by James Long, who was a missionary and later jailed for translating a Bangla play. This was his personal catalogue of books he read and was not a part of the Imperial project of regulating speech in India.

Above right: Norah's library card to access all the archives in the British Library.

Through my project, I improved my archival research skills as most of my work derived from primary sources. I found court cases in the archives that otherwise hadn’t been written about or researched, and, at times, my work felt like uncovering hidden aspects of history. At a certain point, the librarians at the front desk stopped asking for my card when they passed over the archival materials I requested—I was at the British Library that often.

Leading up to my trip, my mentor, Dr. Caz Batten, introduced me to various Penn faculty members and resources. Mitch Fraas, a curator at Penn Libraries, connected me with an archivist at the British Library who walked me through the space on my first day. These pre-research conversations allowed me to strategically utilize my time at the archives. My mentor showed me the importance of connecting with adjacent researchers in your field, even if they don’t have experience in your specific area of research; in many cases, they’re likely familiar with someone else who can help you.

In addition to my research, I worked as an education reporter with Chalkbeat, where I covered the Supreme Court case Mahmoud v. Taylor, which centered on parents’ right to opt their children out of instruction containing LGBTQ+ stories. Speaking to my editor, I drew a direct connection between my reporting as a journalist and my research as an academic. Oceans and centuries apart, the U.S. Supreme Court wrestled with the line between “indoctrination” and “exposure” in children’s books just as British officers grappled with the line to define certain poetry as violent. The heart of these cases seemed to be a question of literary interpretation rather than legal.

Drawing this connection between present and past transformed my understanding of my archival work. Currently, I am in the process of applying to graduate school in the U.K. to continue this project. I hope to apply what I learned through my summer research to better understand how the law interacts with literary interpretation.

Interested in learning more about University Scholars? View other UScholars research experiences on our Student News page!

Related Articles